LIFE AND TIMES OF ALI AKBAR KHAN

Popularly known as Khansahib (as he will be referred to through the course of this article), Ali Akbar Khan was held in high respect as a musician's musician.

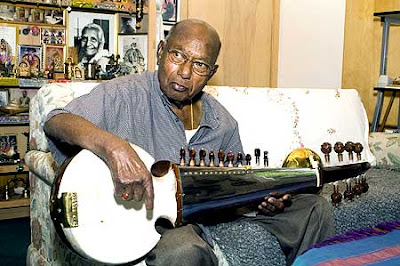

A prolific singer and versatile sarod (a fretless 25 stringed instrument) player - Khansahib, was born in 1922, on April 14th, in Shibpur, present-day Bangladesh to a court musician father - Acharya Baba Allauddin Khan, and a housewife mother, Madina Begum.

Aside from his mastery of music, Khansahib is also fondly remembered for his vast wealth of knowledge. Majoring in Maihar Gharana (ancestral Indian tradition), he rose to become of the greatest classical Hindustani musicians that ever lived a young Khansahib was one who greatness was much expected from, as his father paved the stepping stones for his path to greatness in life.

Taking up studies under his father in vocal music at the age of 3, the young Khansahib went on to study every rope of the classical music of Northern Indian. With a father who was the primary court musician for the Maharaja of Jodpur (Maihar, present-day Madhya Pradesh, India) - Khansahib couldn't pray for a better teacher to tutor and guide him through what would become his life's greatest calling, music.

Northern India's classical music ranks among the oldest musical traditions in the world which have flourished to this day. Acharya Baba Allauddin Khan, Khansahib's father, falls among the greatest Northern Indian classical musical figures of all time. It will interest you to know that, Khansahib's family Gharana (ancestral music) roots can be traced back to Mian Tansen, a revered 16th century musical maestro, who was a top court musician for the great Emperor Akbar. The Gharana was considered as pure magic which when played could cause jaw dropping magical happenings like healing of ailments, bringing of rain, controlling of certain animals, starting of fires etc.

Khansahib was later sent to Bengal after a few years to continue his musical studies in the general understanding of musical rhythm and mastery in the flute and percussion under his uncle, Fakir Aftabuddin Khan. Khansahib spent a few years at his uncle's before returning his father who further tutored him in other traditional Indian musical instruments till he turned nine years old when his father focused all energy on teaching and guiding the young Khansahib to master the sarod, which became his lifelong musical instrument of choice.

Khansahib's father was a strict tutor who was widely known for being a perfectionist. This shaped Khansahib's years of tutelage under his father. Practice sessions, called Riyaaz, would last for as long as 18 straight hours a day, and Khansahib who had two older sisters and a younger one (the popular late Annapurna Devi) would also practice with them but at other times he practiced alone. In his words, Khansahib had the following to say: “He taught me for 20 years after my return from Bengal. I would have to study up to 18 hours a day. In fact, practically all my waking hours would be filled with music. For as much as 15 of these, Baba would be with me. Among other things, Baba also taught me how to teach others, and how to compose music.”

The nature of his rigorous study session moulded Khansahib into a top-notch musical genius. Living a restricted life and yearning to taste of atleast a little of life's frivolity, Khansahib ran away from home on two occasions but was dragged back each and every time, to continue his studies - which took more than 20 years.

Passing on in 1972 - at age 110 - Khansahib's father took it upon himself to continually tutor his son even after he turned a 100 years old - and the genius, Khansahib often times revealed that his father always showed up in his dream to tutor him.

At a musical conference in Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh, India in 1936 - Khansahib was offered the opportunity to grant his very first public performance and he had the following to say about this: “I do not remember much from that because it was quite some time ago. In those days, all the distinguished singers and instrumentalists used to sit in the front row to hear music. They were extremely demanding and would not tolerate mediocrity. Some of them would come to the stage and shout if they didn’t like what they heard. But I remember that after I finished my performance, many of them came up on the stage and hugged me.”

This paved way for a career that spanned his lifetime, and placed him right in the eye of the public because his great talent in music was spotted at that very first public appearance. Khansahib's first public performance catapulted him two years later, to give a recital on All India Radio (AIR), Bombay, India where he was honoured to be accompanied on the tabla by the legendary, Ustad Alla Rakha - and this became a turnaround point in the life of the young rural musician.

January of 1940 saw the young Khansahib give monthly performance on All India Radio. He moved on to become the youngest music Director for All India Radio by 1944, and his tenure saw the birth of the then popular radio orchestra compositions followed by creative solo performances at the station. His early 20s saw him sign a deal with HMV records which saw journey into music recording. In 1943, Khansahib was appointed court musician for the Maharaja of Jodpur on the recommendations of his father.

He worked as court musician for seven years before the rather untimely death of the Maharaja in a fatal plane accident - on his work life in the royal courts, here is what Khansahib had to say: “In Jodhpur, that king wanted to hear eight hours [of playing each day]. My father wanted me to play 18 hours a day. He figured that if he sent me to the court, I’d at least play eight, as you can’t say no to a king. So he sent me there. The Maharajah was two years younger than me. But he died in a plane crash, and so I left. I didn’t resign though, and so I still have good relations, as if I’m in the family. His son built a music room in my name in the palace. That was my last job. Every night I had to play eight hours, sometimes without tabla, just the alap, when the king couldn’t sleep. When he’d fall asleep, the queen would give a sign that now I could go.”

His first title was bestowed on him at the Jodpur palace - Ustad (Master Musician) - one he never bothered to use because he never harboured the idea of there being a master musician. Interestingly, Khansahib wouldn't accept the title from the Maharaja stated a that he wouldn't take on the title of Ustad with his father who doubled as his guru's permission. To this effect the King sent a telegram to Acharya Baba Allauddin Khan who granted his son permission, but Khansahib remained nonchalant about using the title - Ustad - through his life.

In the 1950s, Khansahib's name became a household on after he left Jodpur for Bombay. He was the brain behind many film scores and began this wide trail of film music composition in 1952 with his debut Aandhiyan until his 1993, Little Buddha, film score. His first national hit was his 1945 hit - Raga Chandranandan - which caught the attention of the world and one which he always is remembered for. On his first hit album here is what Khansahib had to say: “Creating a new raga is very difficult. I can’t avoid old ragas, you see. I have to take the help of the other ragas, then give a new face. And there are already so many ragas there…If a new raga is too much like an old one, you get confused. You have to learn to recognize them. You have to learn so many ragas, not just the notes, but the heart of the ragas.”

In 1955, Khansahib on the request of popular concert violinist - Lord Menuhin - who Khansahib met while the later was on tour of India, left India on a visit to both the US and Europe. Khansahib's first visit to the US was rather eventful as gave a rousing performance at New York's prestigious, Museum of Modern Art - here what Khansahib had say on his first show in the U.S: “When I came here in 1955, I met many great musicians, and they hadn’t any idea that India had its own music. I’ve spent more than half my life teaching and playing for people and now many musicians come over to this country to perform, and I never dreamed it would happen like this. I wanted that this music should go everywhere because it can bring peace and love to every human being. That has been my experience.”

Nonchalant about leaving India for the U.S where the style of music was cultured around shorter musical movements which was opposed to the longer musical compositions of classical indian music - Khansahib was motivated with a recording deal with New York's Angel Records where he broke records as the first Indian musician to record a long-playing album titled - Music of India: Morning and Evening Ragas.

Khansahib in later years worked very hard to promote Indian classical music in the western hemisphere. This move began to hit a wave of massive popularity in 1960s. Following the instructions of his father to teach and spread classical Indian music, Khansahib founded the Ali Akbar College of Music, Calcutta, India - in 1956.

Through his life Khansahib was in the forefront of ensuring the widespread of classical Indian music culture around the world. Khansahib founded the Ali Akbar College of Music, California, US in 1967 and founded same school in Switzerland, in 1985. Khansahib taught at many prestigious institutions around the world and with his influence brought many music teachers from India to the west. Interestingly, virtue of his own rigid training which in his later years became a part of his work life as a musicologist, Khansahib taught classical Indian music for over 40 years - In his words: I tried my level best to stay at home (in India) to train people who would be torch-bearers of our gharana, perfected through my father’s untiring efforts. But financial problems stood in the way, and I found I could not do much with my ideas here. Abroad, the experience was rather the opposite. Positive assistance came from all quarters and I succeeded in creating a new generation of Western pupils. There remains every possibility of Hindustani music taking roots in the West in the near future.”

Honored with awards and honors around the world, among which is the highly prestigious, MacArthur Fellowship in 1991, also breaking records with the reception of this award - Khansahib became the first Indian musician to receive the "genius grant;" Khansahib, on reception of the grant had the following to say: “I was very glad that somebody finally recognized me because I had been working very hard composing and playing for many years. I had also trained 6,000 students at my schools. During the 16th century in India, if a musician was favored by the emperor, he would get gifts of money and even small villages. So this is a bit like the modern version of that kind of patronage.”

Through the course of his career Khansahib received 5 Grammy nominations with a National Endowment for the Arts prestigious National Heritage Fellowship - which remains the highest traditional arts honor. Through all his recognitions and awards globally, Khansahib only valued the title his father bestowed on him which was Swara Samrat - meaning the Melody Emperor.

A library was opened in honour of Khansahib by the Ali Akbar Khan College of Music in 2015 called the Ali Akbar Khan library - which houses of 8,000 hours worth of audio and video works of the music genius covering over 40 years of Khansahib's work.

The music legend, Ali Akbar Khan who we all know as Khansahib passed away, on 18, June, 2009 at his country home in San Anselmo, California, aged 87. He is also fondly remembered for his humility and passionate heart, which were qualities that endeared him to the world - especially his many students. In his words: “Music is an international language. It has always been a special significance in the Indian culture and philosophy. According to Hindu belief the creation itself traced back to Nada-Brahma, creation or manifestation of supreme being. Our sages developed music from time immemorial, for the mind to take shelter in that pure being which stands apart from the body and mind as one’s true self. Real music is not for wealth, not for honors, not even for the joys of the mind, but is a path for salvation and realization. This is what I truly feel. This music is for everyone. Like fresh air, or clean water. In old times, when the old maestros sang or played instruments in the temple, all the animals, birds, tigers, lions, everything, anyone came to hear the music."

.png)